Art Blakey Quintet – February 21 1954

Leonard Feather: A Night At Birdland Liner Notes (BLP 5037. BLP 5038, BLP 5039)

"Wow! First time I enjoyed a record session!"

With these significant words, in a comment you will hear on one of these sides, Art Blakey offers an eloquent tribute to the motive that produced this unique series of recordings.

Because Art had organized this constellation of jazz names a while before taking it into Birdland, and had worked up a library of both old and new material, he was able to produce results that transcended the capabilities of a disorganized jam session.

|

| Art Blakey, Clifford Brown, Horace Silver and Gigi Gryce Photo by Francis Wolff |

Because this material was by now familiar enough to the musicians, they were able to express themselves fully and freely. While they could avail themselves of the lack of any time limitation on the performances, they still took no undue advantage, never distorted liberty into license; as a result, there are no 20-minute voyages into tautophony.

And because Birdland attracts the kind of audiences who come to listen to the music rather than to incite violence or tear up chairs, the musicians felt that their offerings were falling on appreciative ears.

Thus A Night At Birdland combines the three elements essential to an enjoyable evening of modern jazz: preparation, improvisation and inspiration. And the greatest of these three is inspiration.

THE MEN...Art Blakey's extraordinary talent antedated his recent public recognition by far too many years. Born in Pittsburgh in Oct. 1919, he played in Fletcher Henderson's band in 1939, worked for Mary Lou Williams when she formed her own combo, drifted to Boston and had his own band there, and acquired a limited measure of fan acceptance when he played in the fondly-remembered, star-rich, Billy Eckstine band of 1944-7.

He has been heard in night clubs and on records with most of the familiar names of the bop era (he traveled the Blue Note circuit with Monk, Milt Jackson, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, Clifford Brown, Kenny Drew) and worked briefly with Duke Ellington, Lucky Millinder and other big bands.

|

| Clifford Brown Photos by Francis Wolff |

Although largely ignored by the jazz historians, Blakey deserves a place along with Max Roach and Kenny Clarke in the annals of modern drumming. As diligently as either Max or Klook, he helped to effectuate the metamorphosis from bass-and-snares rhythmic and tonal monotony to the full use of all the percussion accouterments so essential to modern drumming. Before forming his own group he put in a year with Buddy DeFranco, during which his ability to swing a small group to phenomenal heights was dramatically illustrated.

Art's teammates on A Night At Birdland are all members of what might well be called the Blue Note family. Lou Donaldson's place in the scene was firmly etched with his great work on BLP 5021 and 5030; Horace Silver's two sets of solos on 5018 and 5034 won wide acclaim. Clifford Brown, after co-starring with Lou on 5030 and Jay Jay on 5028, led his own sextet on 5032, and Curly Russell has been such a frequent visitor that we won't even attempt to play the numbers game with him.

THE TIME...Too many records are made under the inexorable pressure of daytime studio working conditions, with half the musicians trying to stay awake after a rough night's work. This session was made between the hours of 11 p.m. and 3 a.m. on Washington's Birthday eve, February 21, 1954, before a large and obviously receptive audience.

THE PLACE...More than any other club since 52nd Street days, Birdland had earned a global reputation through its effort to promote the best in jazz. Situated below street level on Broadway, near 52nd, it was opened in December 1949 and had played host to virtually every major name in the field.

The ebullient voice that starts the session is that of Pee-Wee Marquette, the club's emcee-mascot, who atones in vocal fortitude for all that he lacks in physical stature.

|

| Pee Wee Marquette with The Jazz Messengers Photo by Francis Wolff |

Special thanks are due to Oscar Goodstein, the club's manager, whose genial cooperation made this novel venture possible.

Recorded by Rudy van Gelder, an engineer who understands jazz and knows how to balance it, the session truly captured the spirit of the occasion and the atmosphere of the world's most rhythmic aviary.

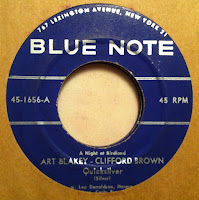

THE MUSIC...BLP 5037 brings a new version of Split Kick, which Horace Silver first wrote and recorded when he was with Stan Getz, as well as a combo version of his Quicksilver, which he made as a piano solo on BLP 5018. Once In A While features a lyrical flight of fancy by Brownie, who at this tempo engages in everything from long, flowing phrases to a flurry of 32nd notes. Listen for the unusual triplet-accent effects in one passage of the accompaniment.

BLP 5038 features a 12-bar blues theme, Wee-Dot, penned some years ago by trombonist Jay Jay Johnson, in which Brownie delivers a tremendous solo. Horace's Mayreh is based on the chords of a well-known song in which all God's children had rhythm. Night In Tunisia is preceded by Art's oral revelation that he was present with Dizzy wrote the tune — "in Texas, on the bottom of a garbage can." The sanitation department can take a low bow.

BLP 5039 offers Lou in ballad mood with a fine solo on the old British standard If I Had You, plus tow familiar themes by Charlie Parker: Confirmation and Now's The Time. The latter, a 12-bar blues, was written some time before the highly successful Hucklebuck.

To quote Art Blakey again, we'd like to close by echoing his opinion that he has surrounded himself with "some of the greatest jazz musicians in the country today." As you'll hear him say on the record — "Yes, Sir, I'm going to stay with the youngsters — keeps the mind active." We might add that at 34, Art is still young in years, in mind and in music, and must surely have many years of success and still greater recognition ahead of him.

Richard Havers – Uncompromising Expression – Thames and Hudson

Blue Note’s first session of 1954 didn’t take place in the studio; it was a live recording at Birdland with the Art Blakey Quintet. The record, which was released as A Night At Birdland, is sensational and Rudy Van Gelder’s skill in capturing the atmosphere generated by a live band that featured Horace Silver, Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson, and Curly Russell on bass makes it one of the best live jazz recordings there is. It was recorded over the five sets played by band that day, and when it was reissued as a 12-inch record in 1956, Billboard reviewed it as follows:

‘Tremendous modern hard bop session cut at the jazz club during working hours in 1954. Although this stuff has been out on 10-inch LPs, the increased market value of the performers, the superior quality of the solos and the prevalent excitement should carry sales as far as Blue Note’s distribution will allow.'

Bob Blumenthal: A Night At Birdland Volume 1 RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes 2001

These performances, taped at Birdland in February 1954, are historically significant for a variety of reasons. They were the first at the famous New York nightclub to be recorded for the specific purpose of release on record, early examples of the benefits of both live recording and the new long-playing record, harbingers of an influential trend in album design, indicators oft the dominant direction jazz modernists would pursue for the remainder of the 1950s, and the seed of an ensemble that would remain consistently important and frequently dominant on the jazz scene throughout the remaining 36 years of drummer/bandleader Art Blakey's career.

Blakey was 34 years old at the time. Given his already sizeable contribution via work with Billy Eckstine's band, Thelonious Monk and Miles Davis, he was a surprisingly unheralded drummer until he won the first Down Beat Critics' Poll as a "new star" in 1953. Alfred Lion of Blue Note Records had long been aware of Blakey's talents, however. Lion had recorded a Blakey Octet in 1947 known as the Messengers due to its heavy representation of Islamic musicians, and had featured the drummer on several sessions with Monk and with James Moody around the same time. In 1952, Blakey's career received a dual boost when he began touring with clarinetist Buddy DeFranco's quartet and assuming the role of Blue Note house drummer. Horace Silver, Miles Davis, Clifford Brown, and fellow DeFranco sideman Kenny Drew had featured the drummer on their sessions for the label during '52-3, and a pair of Blakey/Sabu Martinez duets included on Silver's second LP presaged subsequent percussion-ensemble dates.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

The time had come for Blakey to begin leading his own group, a task he pursued immediately upon leaving DeFranco. Given the depressed nature of the jazz business at the time, overnight success was not an option. The better part of two years would pass before the cooperative quintet that looked back to Blakey's first Blue Note recordings and called itself the Jazz Messengers captured the public's imagination. In the interim, the drummer took what jobs he could find with a core group of compatible players, many of whom had also recorded for Blue Note as leaders. That was the case with everyone on this album except bassist Curly Russell, who, in any event, had made frequent appearances on the label with Bud Powell, Howard McGhee, Fats Navarro, Silver and Drew.

Birdland became a preferred venue for these flexible early Blakey units. One, with Donaldson and Silver as well as Kenny Dorham and Gene Ramey, had been captured on an aircheck three months before the present recordings. Bootleg records made from the club's radio remotes were already becoming common; Birdland had installed a radio wire shortly after its opening in December 1949 and broadcast nationally over the NBC network for a time. Performances specifically intended for release on commercial recordings were another matter, at Birdland and throughout the world of jazz nightclubs, since it was assumed that a combination of crowd noise and the impracticality of making repeated takes in front of an audience would lead to inferior material. As it turned out, the crowd added atmosphere, and the greater relaxation musicians felt when creating outside the recording studio produced music with a level of inspiration that made any momentary lapses in execution incidental.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

These live sounds were waiting to be captured by the rapidly improving recording technology and a new generation of recording engineers, the most jazz-savvy of whom was Rudy Van Gelder. Concert recordings had been gaining popularity since the first Jazz at the Philharmonic releases nearly a decade earlier, but prior to these Birdland tracks there were few examples of actual nightclub sets. Marian McPartland's Hickory House session for Savoy in 1953 may have been first, but these performances really started the club recording ball rolling.

Original annotator Leonard Feather noted that Blakey had assembled both this specific quintet and its music "a while" before the recording, a situation that Feather felt allowed the band to take positive advantage of the extended performance time allowed on LP. These were the first truly long-playing performances Lion produced, as he had filled previous Blue Note albums with takes that could simultaneously be issued as singles. The additional playing time proved crucial, allowing as it did for the sustained intensity of the emerging hard bop approach to be accurately documented for the first time.

From the moment that nine of these tracks first appeared on a series of three 10' albums, they were hailed as classics. The alternate take of "Quicksilver" was added less than two years later when the music was initially reissued in the expanded l2" LP format. Both editions used color-coded versions of the identical photomontage as covers, a look that would define other Blue Note multi-volume sets and was of a piece with trends in contemporary painting.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

Three additional titles and the alternate take of "Wee Dot" were discovered in 1975 and subsequently released. The programming on each volume of this edition of A Night At Birdland presents the material in a sequence matching the initial 12" releases, followed in each instance by two of the subsequently issued tracks.

The proceedings are introduced by Pee Wee Marquette, Birdland's infamous — and extremely short — master of ceremonies who Lester Young once famously dubbed "half a motherfucker." Marquette brings the band on as "Art Blakey and his wonderful group," as the Jazz Messengers name would not be adopted until a Horace Silver studio session in December. The quintet comes wailing right in with "Split Kick," a Silver composition (based on the chord changes of "There Will Never Be Another You") introduced by Stan Getz three years earlier on the pianist's second recording session. This version has a new introduction and a brisker tempo, and it quickly defines the take-no-prisoners approach of this band. Lou Donaldson, clearly of the Charlie Parker school but with a distinctive sound and a penchant for quotation that matches Silver's, is extroverted, fluent and not phased a bit by the assertiveness of the rhythm section. Clifford Brown, already a rising star thanks in large measure to his early appearances on Blue Note, is even more exciting as the ideas burst from his trumpet, his glisses parrying the press rolls from Blakey's tom-toms. Silver, percussive and super-soulful, was made to play in a rhythm section with Blakey, as he demonstrates here to an even greater extent than on his earlier studio albums. Alto and trumpet trade eighths for a chorus, then Blakey plays one that is peppered with his signature Afro-Latin patterns.

Blakey announces Brown's ballad feature "Once In A While," which is as moving as anything the tragically short-lived trumpeter ever recorded. He embraces the melody in the opening chorus, moves over his entire horn with ease, and sustains the lyricism after the rhythm section moves into double time and Blakey exhorts him to "blow your horn!" The three-against-four feeling behind Brown on the second chorus bridge was a favorite Silver device, and Brown's final half-chorus and coda are spectacular.

The introduction heard on the original 1952 trio recording of "Quicksilver" by this same rhythm section is omitted, and the tempo is faster here; but Silver's take on the changes of "Lover Come Back To Me" still feature hilarious inserts of "Oh, You Beautiful Doll" and "Donkey Serenade" in the theme choruses. Brown, whose quotes are less frequent and more esoteric than those of his fellow soloists, gives us a bit of Gigi Gryce's "Salute To The Band Box" on his second bridge, and Blakey adds particularly inspired commentary behind Silver.

"A Night In Tunisia" may or may not have been written "in Texas, on the bottom of a garbage can," as Blakey announces. Composer Dizzy Gillespie said that he came up with the piece and performed it during a 1941-2 engagement with Benny Carter at Kelly's Stables in New York, where it was initially called "Interlude." There is no dispute, however, about the tune's status as a modern jazz classic, thanks to Charlie Parker's Dial recording with its astounding alto break and such subsequent versions as Bud Powell's for Blue Note. Donaldson plays a jaw-dropping break of his own to launch the solos, then sustains the heated atmosphere. Brown begins more carefully, displaying his elevated melodic imagination and sense of structure amidst the hard swinging of the rhythm section. This tempo is ideal for appreciating the charge Silver creates during his solos with those stabbing left-hand accents, like a finger poked in the music's side. Blakey also solos, minus the miscellaneous percussion accompaniment that would become de rigeur in later versions by the Jazz Messengers.

This is the debut recording of "Mayreh," which Blakey would reprise with a totally different quintet three month later in a studio session for EmArcy. Silver based the composition on the changes of "All God's Children Got Rhythm," and the title on the way North Carolinian Donaldson pronounced the name Mary. Ideas simply pour out of Brown's horn, in a solo where the virtuosity is obvious yet never obliterates the musical content. Donaldson, Silver and Blakey also swing hard in what was a set-closer, to judge by the segue into the club's theme, "Lullabye Of Birdland."

"Wee-Dot," the first of two bonus tracks, is an alternate take. The master take of this blues is heard on A Night At Birdland Volume 2. Donaldson wails at length in the opening solo, which features one of his patented string of quotes in the center; then Brown plays an equally heated solo. The churning, relentless force of the rhythm section behind the horn soloists must have sounded startling at the time, but would quickly become central to the hard bop approach. After Silver's choruses, Curly Russell gets a rare solo spot.

Silver begins the next track with a hint that the band may be headed into the blues ballad "Please Send Me Someone To Love," though the more traditional twelve-bar form is revealed once Donaldson begins to blow. The saxophonist shows himself to be the most soulful of Bird's disciples in his choruses, after which Brown also plays some serious blues in which his use of the trumpet's upper register is quite distinct from that of Gillespie and Fats Navarro. Silver completes the sequence with spots of assistance from the horns that grow into a full-blown conversation on the final chorus.

Bob Blumenthal: Volume Two Liner Notes

Curly Russell was the bassist the original 1947 recording of “Wee Dot” by the septet of baritone saxophonist Leo Parker, a band featuring several current Illinois Jacquet sidemen (including Parker and composer J.J. Johnson) and Dexter Gordon in the tenor chair. This master take is the classic recorded performance, however, with Donaldson at his most limber and biting before Brown uncorks a solo that Feather accurately dubbed "tremendous" and Silver provides a veritable precis of his insistent mercilessly swinging and soulful style. No one in this band gave any quarter, as this overdrive performance confirms. Blakey’s remark regarding his enjoyment of the session says it all. (A tamer, though still notable alternate of “Wee Dot" is included as a bonus track on A Night at Birdland Volume One.)

Donaldson gets a ballad feature, as Brown did on Volume One. The alto saxophonist made an excellent choice in “If I Had You," which he dashes through in two choruses. As usual, allusions abound, including the Donaldson favorite "Swinging on a Star."

“Quicksilver” is heard next, in a significantly longer take than the originally issued master. There is less to choose in these performances than from those in "Wee-Dot," and one suspects that the shorter playing time heard in Volume One determined its release on the original 10” LP. As a jazz fan whose early passion for the music was shaped by both volumes of the original I2 LPs, the excellence of this alternate and the joys of both versions (each with a rare solo by Russell) taught me a valuable lesson in the spontaneous aesthetic of the jazz art form.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

The next two compositions are by Charlie Parker. Blakey brings on "Now's The Time" at a bristling medium tempo, which proves ideal for the extended blues inspection of the soloists. The first alto chorus is played over the rhythm section's suspension and ends with a quote of "As Time Goes By," then resolves into straight-ahead tempo with a funky flourish. Donaldson was second to no alto when it came to a straight balance of bebop and soul (others like Cannonball Adderley, Jackie McLean and Phil Woods had older and newer things in the mix), and blows one of his best recorded blues solos. Brown's long, detailed lines and take-charge rhythmic concept make his solo a nonstop adventure, capped by beautiful lower-register work. Silver’s solo contains of the best quotes in both volumes when he works in "Shadow Waltz." This is the performance that elicited the immortal Blakey quote about "stay[ing] with the youngsters... And when these get too old, I'm going to get some younger ones. It keeps the mind active."

"Confirmation" is one of the greatest sets of blowing changes, and the band sounds as if it can't wait to dig into them. In one of the few departures from the session's standard procedure, Brown opens the soloing, and only gains in inspiration as the rhythm section boils beneath him, For this listener’s money, Brown never played better on record than on this solo and the others from the Birdland session. The same might be said for Donaldson, who was clearly on throughout the evening (and in no way intimidated by samples of the oeuvre of his primary inspiration Parker), and for Silver, who let the world know here that his early studio work for Blue Note was no fluke. Blakey dominates a chorus of Russell's walking bass before the theme returns and "Lullabye Of Birdland" and emcee Pee Wee Marquette signal the end of another set.

"The Way You Look Tonight" loses its original tenderness in this hard-blowing version, the first of two bonus tracks. This is the longest performance on either Birdland volume, with three choruses each for Brown (as fluent as ever, if a bit more commonplace in his phraseology) and Donaldson, two by Silver in his best nursery-rhyme vernacular, and one by Blakey. Brown counters the alto sax lead with "Can't Help Lovin' That Man," which he would record with strings in 11 months.

"Lou's Blues" is not the same melody that appeared under that title on Donaldson's first session as a leader for Blue Note in June 1952. At Birdland, the Donaldson blues line is faster and more furious after a fairly mysterious Russell introduction, Alto, trumpet and piano ignite in a performance that, given the stretching-out luxury afforded by the club environment, may have been initially overlooked for being too brief.

Michael Cuscuna: A Night At Birdland Volume 3 LNJ-61082 Liner Notes 1984

Inspired by Chick Webb, Art Blakey began as a powerful and musical big band drummer with Fletcher Henderson and Billy Eckstine. The Eckstine band was, of course, the incubator of be-bop and Art was its master. He brought his own style and dynamics to a school of drumming first defined by Kenny Clarke. By 1947, he was making his own date for Blue Note and powering Thelonious Monk's first record dates.

Alfred Lion in those years was immediately taken by Blakey's richness, soul and strength and would travel to various clubs specifically to catch the drummer. Blakey became a Blue Note regular. But his next opportunity to record did not come until the night of February 21, 1954 with a live session at Birdland. He had organised a band with Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson, Horace Silver and Curly Russell. On other occasions Joe Gordon would play trumpet. According to Horace, this was intended to be a working band, but work was too scarce and the ensemble faded away.

Fortunately, thanks to Lion, it faded away with a secure place in history. Blue Note issued three 10" lps of the music from that night. Later adding an alternate take of Quicksilver, the company issued two volumes on 12" albums (BLP1521 and BLP1522). In the mid-seventies, this writer had occasion to explore the Blue Note vaults and came up with three more tracks, then issued on a US double album with sixties Blakey material. With the addition of the previously unheard Lou's Blues that material is now available herein as volume three of that magic night.

This alternate take of Wee-Dot, a fast blues by J.J. Johnson and Leo Parker, is every bit as exciting and inventive as the first selected for issue. Clifford Brown is especially brilliant, the wat he fashions an intelligent, cogent solo. Typically, Blakey controls the dynamics and provides the fire that spur these men to great statements.

The relaxed, improvised Blues is traditional in form and hints often at the melodies and flavor of Percy Mayfield's best songs. This is Lou Donaldson's finest metier and he turns in a masterful performance, as does the equally soulful Horace Silver.

The Way You Look Tonight is treated to a clever arrangement. Lou plays the song's melody while Brown plays Can't Help Lovin' That Man Of Mine under him as a countermelody. Both songs are from the pen of Jerome Kern. This is a cooker on which everyone is allowed to stretch out, including the drummer.

Released here for the first time, Lou's Blues, a tune which the saxophonist first recorded for Blue Note in 1952. In fact, Silver was the pianist on that version, too. It is an exciting rapid-fire blues, but these men don't just lay into the changes and spew a few thousand automatic notes. They're thinking and creating, even at this tempo. Since the tape machine ran out at the very end of the song as the last note decays, it was necessary to fade the ending. This may indeed have been the reason that it was not included in the initial release.

With these four tunes and the ten on BLP1521 and BLP1522, the entire releasable output of this special occasion is now available.

|

| Photos by Francis Wolff |

One of those dates was a Horace Silver quintet session in November with Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley and Doug Watkins. Within months the co-operative Jazz Messengers were born. Their premise was to present modern, but earthy jazz in a well rehearsed and professional manner. They set the standards for hard bop and spawned a string of great ensembles led by Art and Horace.

This special night at Birdland provides the first documented seeds of that movement. The rare presence of Clifford Brown adds all the more significance to these recordings.

Ira Gitler: Art Blakey – Live Messengers Liner Notes BNLA-473-H2 1978

The tale has been told that once Art Blakey and his Jazz Messengers were traveling from one gig to another when they happened to notice a funeral service in progress on the side of the road. Blakey ordered the car to stop and got out to observe the proceedings.

The presiding minister soon reached that point in the ceremony where he asked, "Is there anyone who would like to say something in behalf of the deceased?"

When no one came forward, Blakey spoke up: "In that case would anyone mind if I said a few words for jazz?"

Now that story may be completely apocryphal but there is no doubt that Art Blakey has been carrying the righteous jazz message to the people for at least as many years as he has used the name Jazz Messengers for his various groups.

First the title was given to a big band known as the 17 Messengers that Blakey organized in 1947; at the end of that year the "Jazz" was added to the "Messengers" for a date on Blue Note with an octet that included Kenny Dorham, Sahib Shihab and Walter Bishop Jr (see December 22 1947). The title was not applied to another of the drummer's groups until 1954 when the quintet comprising Dorham, Hank Mobley, Horace Silver and Doug Watkins began recording for Blue Note. Blakey, the name, and the various personnel who have represented it all have been straight ahead from that point.

The Jazz Messengers have given us many fine recordings over the years but being a great performing band — spearheaded by its super-energetic, super-responsive leader — it has been at its best in a club situation where a live audience can receive the transmissions and rebound them back on to the bandstand. This double LP presents the Jazz Messengers in just that type situation: two different editions; three venues.

To begin at the end might seem out of order but not when you're dealing with a major find — the quintet with the immortal Clifford Brown that taped the fabled A Night at Birdland on Washington's Birthday eve (February 21, 1954) which first was issued on a 10-inch LP and later on two 12-inch LPs. Side four here is devoted to an alternate take of the previously released Wee Dot, the J. J. Johnson-Leo Parker blues that is still a popular jamming line today; and two tracks that are completely new to us, Blues (as traditional as you can get and credited to no one for precisely that reason) and Jerome Kern's The Way You Look Tonight.

This group was not called the Jazz Messengers at the time. It was not one that worked together on a regular basis but with Blakey and Silver aboard it had enough links with the spirit of what the drummer had done and was going to do in the following year to rate an honorary title. Besides when you have a front line of Clifford Brown and Lou Donaldson who is going to quibble over a few Message units?

Brownie and Lou had recorded for Blue Note under Donaldson's leadership in 1953, the same year Clifford had done his own date for Blue Note and one as a sideman with Tadd Dameron for Prestige. After A Night at Birdland he was to join Max Roach as co-leader in one of the most inspired, fulfilling groups in the history of jazz. Two years later he was killed in an automobile crash. He had reached a point of accomplishment only a select few attain, inspiring a whole generation of trumpeters (and other instrumentalists) and thrilling countless listeners with his overdrive attack, golden tone graded from shimmering to brilliant, and essential, unassuming soulfulness. To hear some unreleased Brownie is a rare privilege and the kind of extra special kicks that the untapped jazz library can provide.

The entire group gives off a strong electrical charge. Donaldson was obviously enamored of Charlie Parker but has his own bluesy approach to the idiom. (After a long period of pursuing more of a R&B approach, Lou played the Colorado Jazz Party in the fall of '77 and was leading his own jazz group at Jock's Place in Harlem in the spring of '78.)

Silver had already established himself as a master accompanist, his percussive "comping" like a second, harmonic drummer. After graduating from the Messengers he formed his own quintet of communicators and close to 25 years later is still going strong—with Blue Note, too.

Curly Russell, veteran of 52nd Street, Benny Carter's big band, Gillespie, Parker, Hawkins, Getz, Bud Powell's trio and Tadd Dameron's sextet, played with Blakey in Buddy De Franco's combo in 1952. He was one of the steadiest rhythm players on the New York scene but later dropped out of music after working R&B gigs in the late '50s.

Blakey, in addition to a couple of years touring with De Franco, had been quite visible as the house drummer at Birdland. At the "Jazz Corner of the World' as the basement club was called, he played with everyone, including groups with which he was not completely comfortable. Although he was also well-known and respected for his work with the Billy Eckstine band, Miles Davis and Monk, he truly began to come into his own as a leader with this session in 1954.

This was an all-star jam arranged for the purpose of recording by Blue Note's perceptive president, Alfred Lion. The cast was made up of musicians who obviously enjoyed playing together. This is evident in the immediate fire of Wee Dot Donaldson plunges right in and Brownie follows, Jets open. He knew how to play a phrase, rephrase it or contrast tv.»o similar phrases with leaps from one register to another. He was a master manipulator in the best sense of that word.

A soulful Lou begins Blues in a Parker's Mood groove. Brownie sings in all ranges of his horn. How he could tell a story! Horace gets down with the blues in his inimitable style. I can almost hear Alfred Lion, as he stood by the bar, saying, with that rolled "r" typical of the native Berliner, "Yeah, dot's fenky, cherchy—grroovy."

After Silver's solo the horns come back in to ease on out. The Way You Look Tonight is a burner with Donaldson carrying the theme and Brownie playing another Jerome Kern song — Can't Help Lovzn' That Man of Mine — as a counter-melody. Lou has the bridge but it's Clifford who catapults out of the first chorus to chomp on the meaty harmonic structure. In his third bridge he quotes from The Chase and The Merry Go-Round Broke Down, the way Fats Navarro liked to use it. Lou uses Flight of the Bumble Bee and Country Gardens to launch his third chorus while Horace, In a military mood, paraphrases a bugle call and Over There. Blakey not only takes a dynamic solo but returns on the final bridge to explode once again.

Down Beat 8 September 1954 Volume 21 Issue 18

The first of a series of three LPs based on a session recorded at Birdland on Feb. 21 of this year. Art Blakey was working there at the time with Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson, Horace Silver, and Curly Russell. The set is very well recorded by Rudy Van Gelder, and is one of the better caught-in-a-club sessions on record. Here you even get an introduction by resonant Pee Wee Marquette, the Bert Parks of Birdland and a few words from Art. Silver, Blakey and Russell are excellent in the section work, and Horace solos well. Donaldson plays with more incisiveness than on any of his previous records; the increased vigor affects his tone little adversely, but Lou's authority indicates a young altoist of increasing importance. The brilliant Clifford Brown amply justifies his new star victory in this year's Down Beat Critics' Poll except for one thing, and that's why this isn't five-starred.

Once in a While is Clifford's concerto and it doesn’t quite come off. Reasons: the approach to the tune is interestingly different but there apparently wasn't enough preparation, the alterations come out awkwardly (in the accompaniment, too), and there is therefore the feeling of cluttered rather than flowing structure. Clifford also does not sustain his longer note well; and he has one main trouble on all the tunes - he often plays too many notes. Clifford will be a great trumpeter, not just a very good one, when he finds out the expressive value of economy. But this set is highly recommended, and I'm looking forward to the next two. By the way, notice how this Blue Note LP has much more presence than the other labels producing jazz reviewed in this issue. (Blue Note LP 5037)

|

| Radio Show |

Down Beat 1 December 1954 Volume 21 Issue 24

This is the second of three volumes that resulted from a session one night at Birdland this February. Personnel headed by Art includes Clifford Brown, u Donaldson, Horace Silver and Curly Russell. Wee-Dot is an original by J. J. Johnson and Mayreh is based on All God's Children Got Rhythm. Dizzy's Tunisia, preceded by Art's brief description of where it was written, takes the whole of the second side and lasts a little over nine minutes.

Clifford Brown accounts for this rating, because otherwise would have been a notch lower. For one thing, the LP is not intelligently programmed. There is too similar a texture and tempo all through both sides with no ballad or any other kind of real diversification of repertoire. The result is some feeling of sameness throughout for this listener. This feeling is accented by Lou Donaldson’s alto all the way. Lou, who has been heard to better and more cohesive advantage on Blue Note studio sessions, blows vigorously enough; but too often his choruses are pieced together by cliche fillers, his tone is apt to take on too acrid an edge, and in general, there could be more care in the construction of his idea patterns. Swinging isn’t enough. One interesting point- meant as commendation, not criticism - is the jumpin way Lou comes as a modernized Pete Brown at the beginning of his chorus in Mayreh.

Horace Silver is pulsatingly alive on all three sides, and while his choruses are more inventive than Lou’s, they too could have used some additional attention to construction. But the man certainly drives, and often provides leavening flashes of quick humor. Curly Russell is adequate though not outstanding. Blakey is often imaginative in his backing for individual soloists and never less than exciting. He is not a drummer, however, to accompany introverts, whom he tends to overwhelm, but fortunately none of the hornmen here was intimidated. Brown is dizzily amazing on Wee-Dot, has a good chorus on Mayreh and is most worth listening to of all those present on Tunisia.

Rudy Van Gelder’s recording, particularly for an out-of-studio recording, is first rate. (Blue Note-5038)

Down Beat 9 February 1954 Volume 22 Issue

Vol. 3 of Blue Note's well-recorded, often exciting Night at Birdland series. As on the previous two LPs of this session (all recorded the night of Feb. 21 1954) Art Blakey heads a wailing combo made up of Clifford Brown, Lou Donaldson, Horace Silver, and Curly Russell. All blow well here, and Donaldson has some of his better choruses in the series, including the featured solo on the one ballad in the set.

The other two compositions are neo-classics by Bird. Now's the Time runs for 8:20 and Confirmation at 8:25 takes the whole second side, plus a closing announcement by Pee Wee Marquette. Almost the LP is made up of solo work which is just as well for the little ensemble work heard is raggedy. The three volumes as a whole make a sturdy tribute to the drumming fire and perennial youth of Art Blakey who comments at the beginning of this third LP: "Yes, sir, I'm going to stay with the youngsters. When these get too old, I’m going to get some younger ones. It keeps the mind active." (Blue Note 5039)

|

| Gigi Gryce, Clifford Brown |

Down Beat December 16 1953 Volume 20 Issue 25

Nat Hentoff Interview with Art Blakey

Art Blakey, who most recently traveled the country with Buddy DeFranco, now has his own quintet that includes altoist Lou Donaldson, Kinny [sic] Dorham, bassist Gene Ramey and pianist Horace Silver. Interviewed in New York, he had a few things to say about jazz in general and the behavior of musicians in particular.

“We’re trying to build up a group that has that good old jazz feeling. We want to blow and have a ball and make mistakes, if necessary, but have that good feeling that used to be in jazz. Remember Davey Tough? That’s what I mean.

Like Good Dixie

“We’re trying, “ Art Blakey continued, “to get the same thing they do in good Dixieland. We’ll certainly play modern, but we want to get the people to follow the beat and let the horns do what they want to. Once they follow the beat, they’ll be able to follow the horns, too. And I’d as soon just call it jazz and forget the labels.”

At 33, Art has a family of four including a 17-year-old daughter at Hunter college who is studying to be a pediatrician. Another girl is 15, his son is 13, and there’s a seven-month-old little girl. “I think my son is going to be a musician. I wish he would. Music broadens a man’s scope on life and as for me, I sure can release a lot of my tensions by expressing myself through the drums.”

Discussing the tensions that beset jazz musicians, he had this to say: “As soon as modern musicians straighten themselves and their lives out, we can really present our music to the public. The public loves presentation. But when fellows on the stand seem to be asleep when they’re not playing, when their appearance is bad, it’s bad for modern music. The older jazzmen, by and large, are clean, alert, and have a good appearance, and so have been able to outsell us.

“Do you remember how at first modern jazz drew good crowds, but as the people saw the attitudes and appearance of some of the musicians, the box office fell? People would say: ‘Why should I go to see men who look like they’re half asleep?’

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

‘Brought It On Ourselves’

“Let’s be frank. A lot of the public has a whole set of ideas about what a modern jazzman is like, and we brought it out on ourselves. And more important than the effect on the public is the fact that a man

is really committing suicide when he falls into dope. And you don’t need it. At anytime. All you is eight hours sleep and a meal. and you can blow your best.

"But its getting more encouraging all the time. Most of the musicians who were involved are waking up. I think we're ready now. And I hope this group will get some bookings so we can show we're ready.”

The Blakey quintet broke in at the French Quarter in New York, did a week at Birdland opposite the Modern Jazz Quartet, another week at the Rendezvous in Philadelphia and then filled in with one-niters in Long Island and Boston until they opened in Chicago at Nob Hill for three weeks. The band will record for Blue Note, is booked by Joe Glaser, and managed by Oscar Goodstein.

Notes etc.

Marc Myers interviewed Rudy Van Gelder for All About Jazz. Some recollections of the Birdland date can be found here: https://www.allaboutjazz.com/news/interview-rudy-van-gelder-part-4/

Bob Blumenthal examines the sessions in further detail here: https://www.mosaicrecords.com/the-great-jazz-artists-art-blakey-a-night-at-birdland/

Session Information

Art Blakey Quintet

Clifford Brown, trumpet; Lou Donaldson, alto sax; Horace Silver, piano; Curly Russell, bass; Art Blakey, drums; Pee Wee Marquette, announcer.

"Birdland", NYC, 1st set, February 21, 1954

Pee Wee Marquette's intro,

tk.1, Wee-Dot (alt), Blue Note BN-LA473-J2

tk.2, Now's The Time, Blue Note 45-1678, BLP 5039, BLP 1522

tk.3, Quicksilver, rejected

2nd set

tk.4, Confirmation, Blue Note BLP 5039, BLP 1522

tk.5, Once In A While, Blue Note 45-1656, BLP 5037, BLP 1521

tk.6, Mayreh, Blue Note BLP 5038, BLP 1521

3rd set

tk.7, Our Delight, rejected

tk.8, If I Had You, Blue Note 45-1657, BLP 5039, BLP 1522

tk.9, Split Kick, Blue Note BLP 5037, BLP 1521

tk.10, Lou's Blues

4th set

tk.11, Wee-Dot, rejected

tk.12, A Night In Tunisia, Blue Note BLP 5038, BLP 1521

tk.13, Quicksilver (alt), Blue Note BLP 1522

tk.14, Confirmation, rejected

5th set

tk.15, Blues (Improvisation)

tk.16, The Way You Look Tonight

tk.17, Wee-Dot, Blue Note 45-1657, BLP 5038, BLP 1522

tk.18, Quicksilver, Blue Note 45-1656, BLP 5037, BLP 1521

Lullaby Of Birdland (finale)

No comments:

Post a Comment