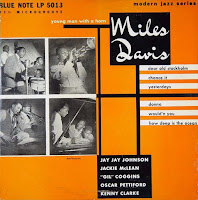

Miles Davis All Stars – May 9 1952

Leonard Feather – Miles Davis Volume 1 Liner Notes – November 1955

AT THE END of 1955 Miles Davis received an unexpected Christmas gift. For the first time, the readers of Down Beat had elected him to first place on trumpet in the annual popularity poll. At that, it was a close race, with only a few votes separating him from the next two eligibles.

That this token of esteem was long overdue can be gauged by the fact that Miles, as far back as 1947, won a poll in which the voters were not the public but a handful of critics, who selected him as the new star of the year in the Esquire balloting. (He tied with Dizzy in this year's Down Beat Critics' poll, too.)

Poll victories, however, are a reflection neither of success nor of artistic merit. Miles' talent is its own best reward, for the music you can hear between these covers stands a good chance of lasting long after the details of the voting are forgotten.

Miles Dewey Davis - born Alton, Illinois, May 25, 1926, raised in East St. Louis, Dizzy and Bird admirer when the old Eckstine band passed through town, Julliard student in,1945, Fifty Second Street denizen, big band sideman with Eckstine and Benny Carter-is a singular human being. Today's leader is always yesterday's follower. Just as Dizzy Gillespie was the chrysalis that grew from an Eldridge egg, so was Miles the butterfly that emerged in the next stage of stylistic development. In fact, so swiftly did his own style develop that it is hard to remember back to the time when Miles' solos seemed to bear a resemblance to Dizzy's.

Wasn't it Barry Ulanov who once wrote that Miles' tone reminded him of a man walking on eggshells? If not, let whoever it was come forward and take a bow, for nothing could more aptly conjure up the manner in which Miles' notes emerge from the bell of his horn, the staccato yet fluid drive of his rhythmic conception. Melodically it would be harder to express his personality in words; one can only observe that if Dixieland is, as it has so often been called, "happy music” then the solos of Miles Davis more likely reflect the complexity of the neurotic world in which we live. The soaring spurts of lyrical exultancy are outnumbered by the somber moments of pensive gloom.

|

| Jackie McLean and Miles Davis at a rehearsal for the May 9 1952 session |

How can you prove it? Miles uses the same twelve notes every other living jazzman uses. Who can say that this music is happy and that music is sad? That Miles can be so completely Miles that Dizzy's Woody'n You assumes a new and un-Gillespieish coloration in his hands?

You can't prove it. All you can say is, well, that's what makes jazz the exciting thing it is, limning the character of the man who makes it, fabricating moods and transmitting thought vibrations in the very moment of creation. And in this process Miles is a past master.

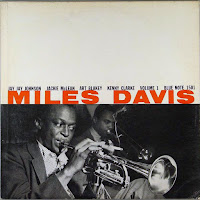

Bob Blumenthal – RVG CD Reissue Liner Notes – 2001 (5 32610 2)

Few musicians in jazz history began their careers as leaders in the recording studio as auspiciously as Miles Davis. The first discs that bore his name found him at the head of Charlie Parker’s quintet for Savoy in 1947, with Bird himself playing tenor saxophone. Then came the three Nonet dates Davis cut for Capitol in 1949-50, later to be known as Birth Of The Cool, which have also been released in the RVG Series. These innovative sessions made a strong impression, and led to three straight victories for the trumpeter in the Metronome polls of 1951-3.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

Yet even as he amassed awards, heroin was bringing Davis to the lowest point of his career. He rarely worked and his musicianship suffered. The recordings he made for Prestige and Blue Note in this period are generally uneven and frequently sluggish. At the end of 1953, he returned to his family’s home in Illinois and overcame his addiction. By late winter of 1954, he was back in New York, poised to realize further triumphs in a career that would last another four decades. This collection, the first of two that feature all of the music Davis recorded under his own name for Blue Note, finds the trumpeter on both sides of that crucial trip home.

The first session was recorded during a year that Davis biographer Ian Carr has described as generally “empty and miserable”, a judgment that the music bears out in part. Certainly the rhythmic snap of Davis’s best previous recordings is absent, and the material in general is less forward-looking than one had come to expect on his sessions. The band, however, represented one of Davis’s best ensembles, with established innovators paired alongside promising youngsters. Drummer Kenny Clarke was arguably the first modernist, and bassist Oscar Pettiford had been the leading voice on his instrument since the death of Jimmy Blanton. J.J. Johnson held a similar position among trombonists, and had worked with Davis previously in both Parker’s band and the Nonet. The new generation was rep resented by two young Harlem musicians, alto saxophonist Jackie McLean (who had made his recording debut seven months earlier on a Davis session for Prestige) and pianist Gil Coggins. The six titles were initially released on 78 singles, and in the 10” LP Young Man With A Horn. The session also produced three alternate takes, which are programmed here after the six master takes.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

“Dear Old Stockholm” is the lone sign that, despite his problems, Davis was looking ahead. The melody is an old Swedish folk song that his friend Stan Getz had recorded a year earlier during a Scandinavian tour under its original title, “Ack Varmeland Du Skona” (Oh. Varméland, Thou Fairest). Davis added a vamp between melodic stanzas, plus a suspended ending to each chorus. He takes a full solo chorus, then splits another with McLean (green but already a recognizable personality) and Johnson on a more deliberate version of what would become a classic arrangement in the hands of the 1956 Miles Davis Quintet.

Pettiford’s “Chance It” is one of several backward glances in this collection to the early days of bebop. The tune had been recorded under the title “Max Making Wax” on Charlie Parker’s notorious 1946 Lover Man session for Dial, with Howard McGhee on trumpet. The alternate was recorded before the master take (as were the other alternates in this collection) and has some rough moments when McLean’s reed squeaks and the rest of the rhythm section fails to enter for Davis’s fours with Clarke. Things are generally more centered on the master take, including the arranged interludes that take Davis into and through his two choruses, Mclean’s affinity for his neighborhood friend Sonny Rollins is particularly clear when he blows in the alto’s lower register.

“Donna,” credited to Mclean here, had been identified as a Davis composition when it appeared at a faster tempo under the title “Dig” on the trumpeter’s October 1951 sextet session with McLean and Rollins for Prestige. Under either name, it is a new melody based on the chord changes of “Sweet Georgia Brown.” The band gets a strong medium-tempo groove going that allows Pettiford to show both his rhythmic strength and melodic imagination; and Davis and McLean bear down in their choruses with the altoist beginning his statement on both takes by quoting Parker’s “Sweet Georgia Brown” solo from the 1945 JATP recording. The master is a bit brighter in overall mood.

|

| Photo by Francis Wolff |

The Dizzy Gillespie standard that follows has been subjected to many spellings, including “Would’n You” on the original Blue Note release. The piece, written by Gillespie for Woody Herman, should properly be rendered as “Woody ‘N’ You.” There is a hint of its big band origin in this arrangement, with countermelodies on the theme statement and Johnson and Mclean riffing behind Davis’s solo chorus. Johnson and Pettiford also split a chorus before Davis’s returns, blowing on the bridge. There is a momentary nod to Gillespie during Davis’s solo on the master. This is another composition that the 1956 Davis group would revisit.

Two ballads by Davis and the rhythm section complete the date. The trumpeter had participated in a Lee Konitz session for Prestige 14 months earlier where “Yesterdays” was recorded, contributing a strong introduction and coda on that occasion. Here he lets Coggins open, then takes over for three choruses. There is some uncharacteristic double-timing during the second chorus, but otherwise the performance features the ballad sensitivity that was already a Davis trademark.

|

| Oscar Pettiford, Miles Davis and Gil Coggins Photo by Francis Wolff |

Charlie Parker had recorded “How Deep Is The Ocean?” at his final session for Dial in 1947. On that occasion, guest J.J. Johnson (24 bars) and Davis (eight bars) split a solo chorus. This time the trombonist lays out, and Davis carries the performance after a lovely Coggins intro. While the mature Davis sound is not yet present, and the melodic shapes are more symmetrical than we would come to expect in the trumpeter’s later work, the haunting emotional climate is unmistakable.

Peter Losin – Session Notes

The original material on Peter Losin’s excellent Miles Davis Reference site here:

http://www.plosin.com/milesAhead/Sessions.aspx?s=520509

This is Davis's first Blue Note session, and the only studio session from 1952. His addiction made him unreliable, and his contract with Prestige had not been renewed. He had no working band. On the few live performances dating from this period he is a guest soloist -- with Jimmy Forrest's band in St. Louis, or with Beryl Booker's quintet at Birdland. He and Jackie McLean were booked for a week at Birdland the week before this session took place, and soon afterward Davis would participate in a touring revue called "Jumpin' with Symphony Sid" (with MC Sid Torin and including Don Elliot, Milt Jackson, Percy Heath, and others) -- in the remaining months of 1952 they were booked in Boston, New York, Toronto, Atlantic City, and several cities in the Midwest.

"Dear Old Stockholm" is based on the Swedish folk tune "Ack, Värmeland du Sköna." Davis modified the tune by adding a pulsing vamp between choruses, and by rhythmically suspending the ending of each chorus. He plays a full chorus, beautifully laying out the haunting melody; and the final chorus is split among McLean, Johnson, and Davis before the theme is re-stated.

"Chance It," credited to Davis, is really Pettiford's "Max is Making Wax," which had been widely performed and recorded by Charlie Parker and others throughout the late 1940s. It would remain in Davis's live book well into the mid-1950s. The alternate take is ragged in places (as when Davis and Clarke begin their four-bar exchanges without the rhythm section [1:55]), and McLean has some reed problems (e.g. at 1:33). But Davis's two choruses are inventive. Johnson does not solo on the alternate take. He does on the master -- he and McLean split a chorus after Davis's solo -- and things are much tighter. Davis's staccato phrasing is impressive.

"Donna" is the same tune credited to Davis when it was first recorded (at a faster tempo) for Prestige in October 1951. It's based on the changes of "Sweet Georgia Brown." This version compares poorly to the one recorded seven months earlier for Prestige. On the alternate take, Davis has the first chorus, McLean the second. McLean's solo begins by quoting a phrase from Charlie Parker's solo on "Sweet Georgia Brown" from the January 1946 Jazz at the Philharmonic concert (compare 1:33 here with 2:06 from Parker's JATP solo). Pettiford takes brief solos at the bridges of the opening and closing choruses. The structure is the same for the master take: Davis (1x), McLean (1x -- his solo begins with same quotation of Parker at 1:34), and Pettiford's solos on the bridges of the opening and closing choruses.

|

| J.J. Johnson and Miles Davis Photo by Francis Wolff |

"Woody 'n' You" was a live staple for Davis in the 1950s, and he continued to perform it at least until 1958. The definitive version is probably that recorded for Prestige in May 1956. here, both alternate and master takes have the same structure: after an introduction by the rhythm section, Davis takes the first chorus, with periodic riffing underneath by Johnson and McLean; Johnson and Pettiford take the next chorus; and Davis returns for the closing chorus.

"Yesterdays" was recorded at a Lee Konitz-led Prestige session in March 1951, where Davis did not solo. Here, after Coggins's brief introduction, he is the only soloist, and takes three solid choruses. It's too bad Davis didn't perform this tune more often.

Davis's only other recording of "How Deep Is the Ocean?" dates from December 1947, with the Charlie Parker Quintet and guest J.J. Johnson. On that occasion Davis took only a short eight-measure solo. Here he is the only soloist.

On May 31 a "gala affair" took place at the Union Park Temple in Chicago, where the "new king of the trumpet," Miles Davis, performed "with 2 bands." (No mention of the personnel, unfortunately.) An All-Star group comprising J.J. Johnson, Milds Davis [sic], Milt Jackson, Zoot Sims, Percy Heath, and Kenny Clarke, along with Symphony Sid Torin, "New York's Greatest Disc Jockey," was booked for a week (June 30-July 6) at Cleveland's Ebony Club.

Thanks to Bruno Leicht for helpful comments on this session.

Richard Cook - Blue Note Records – Secker and Warburg 2001 pp 55-56

Perhaps Blue Note unlucky with Davis. His first date for the label took place on 9 May 1952, right in the middle of what was a desperate year for the trumpeter: he was without a regular band and suffering from a chronic heroin addiction. Lion labelled the session as by the 'Miles Davis All Stars', but with the unremarkable Gil Coggins at the piano and the young and raw Jackie McLean on alto, the appellation was wishful thinking. 'Dear Old Stockholm', the first title, goes off at a lugubrious pace which even Oscar Pettiford and Kenny Clarke seem unable to lift. 'Chance It' is a fast bop line which Davis seems harried by. He turns Dizzy Gillespie's usually ebullient 'Woody 'N' You' into an almost funereal episode. and though the ballad features 'Yesterdays' and 'How Deep Is The Ocean' have some of the cracked melancholy which Davis's admirers set the greatest store by, they're nothing like as good as his comparable playing in his forthcoming Prestige years. For one thing, Davis plays too many notes: the baleful economy which he would later bring to bear on his music is notably absent. As little space as he gets, its arguably J. J. Johnson's trombone playing which offers the most interesting music.

Down Beat 24 September 1952 Volume 19 Issue 19

The Gillespie original, and the traditional Swedish air brought over here by Stan Getz, afford solo opportunities for J. J. Johnson and altoist Jackie McLean, both of both of whom cut Miles on these sides. Neither opus, however, gets the feeling of the tunes as well as the original versions. Rhythm is by “Gil” Cogins and Kenny Clarke with Oscar Pettiord, who has a solo on Would’n. (Blue Note 1595.)

Down Beat 11 February 1953 Volume 20 Issue 3

Miles’ environment here: J. J. Johnson, trombone; Jackie McLean, alto; Gil Coggins, piano, Kenny Clarke, drums, Oscar Pettiford, bass. Swingingest sides are Donna, a comely McLean variant on Georgia Brown, and Chance It, an old opus by Oscar also known as Something for You and Maz Is Making Waz. Though Miles’ articulation and intonation are still sometimes bothersome, his two slow solo sides, Yesterdays and Ocean, are long on ideas. J. J., McLean, and especially Oscar have some good solos. (Blue Note 5013)

Miles Davis, trumpet; Jay Jay Johnson, trombone; Jackie McLean, alto sax; Gil Coggins, piano; Oscar Pettiford, bass; Kenny Clarke, drums.

WOR Studios, NYC, May 9, 1952

BN428-1 tk.2, Dear Old Stockholm, Blue Note 1595, BLP 5013, BLP 1501

BN429-2 tk.5, Chance It (alt)

BN429-3 tk.6, Chance It, Blue Note 1596, BLP 5013, BLP 1501

BN430-0 tk.7, Donna (alt), Blue Note BLP 1501

BN430-1 tk.8, Donna, Blue Note 1597, 45-1633, BLP 5013, BLP 1502

BN431-2 tk.12, Would'n You (alternate master), Blue Note BLP 1501

BN431-3 tk.13, Would'n You, Blue Note 1595, BLP 5013, BLP 1502

BN432-0 tk.14, Yesterdays, Blue Note 1596, BLP 5013, BLP 1501

BN433-0 tk.15, How Deep Is The Ocean, Blue Note BLP 5013, BLP 1501

No comments:

Post a Comment