Benny Morton’s All Stars – January 31 1945

Eugene Chadbourne – bluenote.com Benny Morton biography

The trombone was a particularly effective musical device in swing music, and not only for its slurs, slides, growls, and groans. Benny Morton was known for his beautiful tone, advanced use of chromatics outside of the key signature, and tasteful understatement. He took part in much of the essential music of the swing period; in fact, listeners undertaking an exploratory journey into the heart of swing music will run smack dab into the man wherever they may turn. For example, dig into the limited but miraculous discography of innovative electric guitarist Charlie Christian and Morton is right there bopping along. One doesn’t have to be a jazz fan to appreciate the ’30s and ’40s recordings of vocalist Billie Holiday and Morton is one of the many great players whose contributions make these sides such pearls. He played with Fletcher Henderson and Count Basie and was the member of several of the best swing revival bands from later decades. He kept being invited out on choice gigs well into his ’70s, yet tends to be seen as an undersung hero.

Despite all his fantastic contributions to landmark recordings, Benny Morton just isn’t that well-known a name among jazz fans, unless one is talking to trombonists. He had a huge influence and has been cited as one of the great players by the likes of Kai Winding, Bill Watrous, and Eddie Bert, all top-flight doctors of the bone. The latter man even stopped Morton on the street outside a club and asked him for lessons. Morton obliged, inviting the then star-struck young man backstage to meet his heroes in Basie’s band. He began playing trombone as a child, picking up most of his knowledge on his own. The Jenkins Orphanage Band was his first ensemble experience, although it is not clear whether the man himself was abandoned, which has been known to happen if parents get wind that their child might grow up to be a jazz musician. The trombone soloist in Mamie Smith’s band, Dope Andrews, is said to be the first jazz player who caught Morton’s ear. In 1923, Morton joined Clarence Holiday’s band. Three years with this outfit and he was ready to take on membership in the innovative Fletcher Henderson band, the first of a series of first-rank big bands that he would join, usually for extended stays. He was with Don Redman for six years and Count Basie for three, getting in on many Billie Holiday recording sessions that a handpicked crew of Basie alumni were involved in. He also worked with the orchestra of Chick Webb. Another notable credit was in the orchestra recordings of composer and arranger Raymond Scott, whose work was often used as the background for cartoons. In 1940, he made the transition toward smaller combos, becoming a member of a sextet led by pianist Teddy Wilson. This group has a reputation as one of the superior swing bands of its time and a great vehicle for the leader’s abilities both as a pianist and a bandleader. In 1943, Morton joined another small band, this one led by Edmond Hall. One of the few dates with Morton as a soloist was done in the early ’40s, a 78 for Columbia that was a kind of trombone special. Morton had the A-side with his rendition of the “Gold Digger’s Song,” better-known as “We’re in the Money,” while the flip side featured fellow trombonist J.C. Higginbotham and the accurately titled “Hot Trombone Blues.” Morton left Hall’s band with designs on starting his own outfit, which he kept going for a few years before seeking the economic protection of employment in New York theater pit bands. Through this, he connected with many radio and recording studio band jobs, which largely kept him busy through the ’50s and ’60s. This type of career sometimes heralds the end of a player’s involvement with creative jazz, but Morton kept his slide in with record dates involving players such as trumpeters Buck Clayton and Ruby Braff. There was enough work on the jazz scene by the end of ’60s to allow him to focus totally on swinging, and his accomplishments tell the story of a trombonist going out in a blaze of glory. He wasn’t concerned with in-fighting amongst various branches of the swing genre and played happily with many artists of his generation. The Saints & Sinners band put him together with swing veterans such as Yank Lawson, Bob Wilber, and Bud Freeman. These seasoned jazz pros enjoyed the good life on tour, dining on gourmet sea food while gigging at the Pescara Jazz Festival in Italy in 1974. The Top Brass tour combined Morton with Clark Terry, Bob Brookmeyer, Doc Cheatham, and Maynard Ferguson to create a comprehensive overview of jazz brass, backed by a British rhythm section. He also worked with Wild Bill Davidson, Bobby Hackett, and Sy Oliver. Morton’s collaborations were too numerous and wide-ranging to be collected all in one place, but the Melodie Jazz Benny Morton 1934-1945 definitely pulls in some choice stuff, including dates with drummer “Big” Sid Catlett, trumpeter Henry “Red” Allen, clarinetist Barney Bigard, and tenor sax king Ben Webster. Morton’s side of the Columbia single is included on this set. The Mosaic series also created a re-release collection of the Blue Note Swingtets, a project Morton created with clarinetist Jimmy Hamilton that also featured swing maestros Tiny Grimes and Ike Quebec.

The Stoutonia Volume 35

On Blue Note: The Sheik Of Araby and Conversing In Blue. These sides feature Benny Morton’s All Stars – the trombone of Benny Morton; Barney Bigard’s clarinet, Ben Webster on tenor; Sammy Benskin, piano; Israel Crosby, bass, and Eddie Dougherty, drums. The first side is done in a fast tempo, strictly hot jazz, with practically every instrument participating in solos. On the reverse Webster and Bigard are featured in a Chicago Blues style.

The Record Changer April 1946

Conversing in Blue is strictly a modern record. In it the musicians have achieved the fullest in improvisation without any of the stereotype of arranged jazz. The richness of intonation and the running machinery of a band have great sustaining qualities. When we do away with the best in sound quality and reduce the rhythmic section to an implied beat we are left with only the melodic line. Conversing may not have a highly significant run of solos but they do represent in their outline the workings of melodic emotion. Conversing reveals some bad taste on the part of Webster and Bigard. Biigard is not happy in his choice of the long piercing note followed by a velocity descent into chalumeau. This side is unique in certain moods that it achieves and in the degree of melodic interest sustained.

A flexible trombone rhapsodic passage leads into an interesting introduction by Crosby. Morton starts the cues with a long pick-up. His solo keeps up great activity while Bigard's two choruses are more relaxed. Webster enters his section with energy, and plays two very fine choruses except for his forced vibrato.

The last chorus is quite unique in many respects. Although at first it seems as though Webster were finishing this side, later a "far away" feeling is induced by a nostalgic spirit in the ensemble playing. Benskin's blues piano is the modern tremolo blues associated with Avery Parrish. It is not as satisfying as his playing on the next side.

Sheik of Araby consists of two-chorus solos for the most part. Although Morton's solo is constructed well as a whole, Benskin shows something more than fast 52nd Street piano. He has some good phrases that stand out. There must be something really harmonically different to make this brand of playing really satisfying. Webster uses some atonal high notes that detract from his playing.

Stanley Dance- The Benny Morton and Jimmy Hamilton Blue Note Swingtets

Uniting (Morton) with Bigard and Ben Webster was a stroke of genius on Alfred Lion’s part, for Morton himself had all the qualities that would have fitted him to play in the Duke Ellington orchestra. The instrumentation of trombone, clarinet, tenor and rhythm is unusual. But this disciple of Jimmy Harrison inherited much of Louis Armstrong through him, and was therefore equipped to play lead in an ensemble.

MY OLD FLAME was made by Duke Ellington in 1934, when his band played in a Mae West movie, Belle Of The Nineties. The first chorus of this version, which Morton and Bigard split, is full of Ellington echoes, not merely because Bigard was inescapably himself, but because the versatile Morton, using a felt hat as a mute, suggests no one so much as Juan Tizol. Ben Webster follows, improvising with emotion and swinging gently. Sammy Benskin takes the release, with assured ideas and a pleasing touch, before the leader returns.

CONVERSING IN BLUE is a contrast that incidentally shows how Morton and Teagarden were jointly related to Jimmy Harrison. The tough, gutty opening chorus by Morton is splendidly backed by

Benskin. Bigard and Webster then have two choruses each, the latter building a declamatory statement with floating high notes. Morton returns with mute for a subtle dialogue with Bigard. Benskin proves himself to be an accomplished blues player, replying to everyone and complementing everything with accuracy and graceful strength.

On THE SHEIK OF ARABY, the tempo moves up, but Morton's relationship to Teagarden and Harrison remains plain enough in his two vigorous choruses. Benskin has two in which he seems to have already been intrigued by bop innovations; his solo, as a consequence, lacks a little of the easy, natural flow felt in his accompaniments and on the blues. Webster and Bigard are their exhilarating selves again, and then the three horns chase each other home with fours in the final chorus. The alternate take follows the same routine, but there are interesting differences in the solos, notably in Morton's opening choruses. Here he plays more like Louis Armstrong, confident and relaxed.

LIMEHOUSE BLUES is another number Bigard must have remembered from his Ellington days. Alien a smooth ensemble chorus, he takes two, deploying all his unique devices with a kind of Gallic vivacity. Morton is next, playing open with brisk attack and firm tone. Webster surges on irresistibly with two more, and then Benskin takes one in which Tatum's influence manifests itself very agreeably. Bigard returns and rounds off the performance with the same mock Oriental motif that introduced it.

In sum, it is a successful session, Israel Crosby's supple bass and Eddie Dougherty's good time and accents contributing valuably. Morton's facility and his ability to do whatever he wanted to do are

admirably demonstrated. He had a lead man's feeling for a beautifully distilled statement delivered with good tone. He could play with heat, strong attack and a commanding sense of the beat on up tempos. And he could be properly down and plaintive on the blues. Few trombone players had that kind of versatility.

Dan Morgenstern – The Blue Note Swingtets CD Liner Notes

“The Sheik”, even then a vintage number, opens with Morton’s smooth and always-in-tune trombone. This big band veteran (Fletcher Henderson, Basie, Benny Carter) could always be counted on to deliver. Benskin’s been hearing bop, Bigard is his flowing self, and Ben cops honors, gruff and swinging. The horn fours are kicks. “Conversing in Blue” is one of those Blue Note special excursions on slow blues in a 12-inch 78 format, allowing the players more elbow room and relaxation. Morton’s heard twice, first open, then muted with Bigard, whose beautiful tone is much in evidence. But once again, it’s Ben who takes the prize – he was peerless in the blues, and always had a story to tell, straight from that big heart.

Down Beat March 25 1946 Volume 13 Issue 7

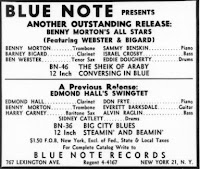

Morton’s trombone, Barney Bigard on clarinet and Ben Webster on tenor are featured on this Blue Note 12-inch. Sammy Benskin, piano; Israel Crosby, bass; and Eddie Dougherty, drums are also on: Conversing In Blue and The Sheik of Araby (Blue Note 46)

Benny Morton, trombone; Barney Bigard, clarinet; Ben Webster, tenor sax; Sammy Benskin, piano; Israel Crosby, bass; Eddie Dougherty, drums.

WOR Studios, NYC, January 31, 1945

BN219-0, My Old Flame, Blue Note 47, BLP 5001

BN220-0, Conversing In Blue, Blue Note 46, BLP 5027

BN221-0, The Sheik Of Araby, Blue Note 46

BN221-2, The Sheik Of Araby (alternate take)

BN222-0, Limehouse Blues, Blue Note 47, BLP 5027, B-6507, BST 89902

No comments:

Post a Comment